UK Inflation 2025: Causes, Policy, and Outlook

Inflation in the UK is finally easing, but it remains above the Bank of England’s 2% target. This article explains why it happened and what to expect in the coming months.

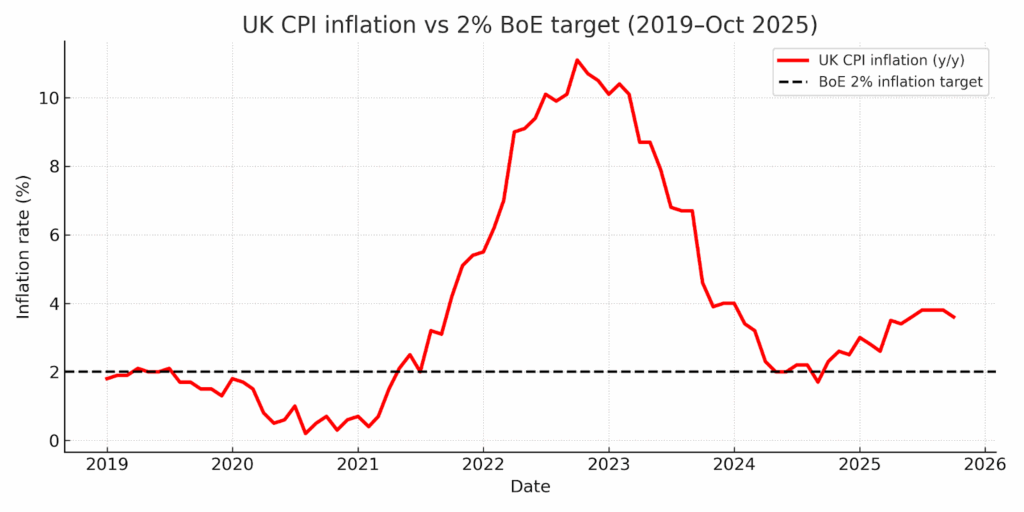

Where Inflation Stands Today

UK inflation fell to 3.6% (YoY) in October 2025, down from 3.8% in September, which marks the first decline in the CPI since May. Reuters

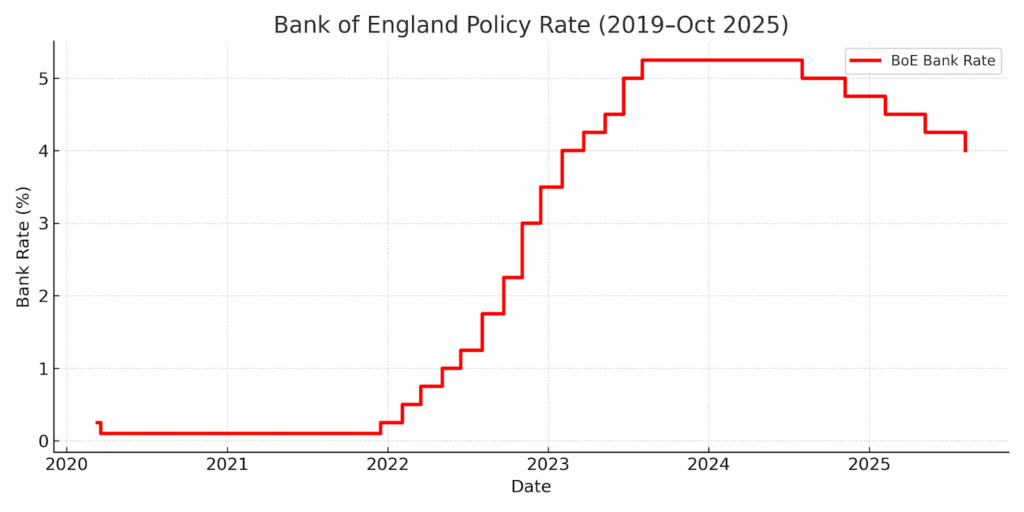

In its 6 November 2025 meeting, five of the nine MPC members voted to keep the Bank Rate at 4% rather than cut it to 3.75%. Bank of England

Given the current inflation, above the target of 2% that the MPC 1are targeting, the BoE has several monetary policy tools to apply to adjust it.

The results of the next scheduled MPC meeting will be announced on 18 December, many investors expect the MPC to cut the bank rate. UK Parliament , Fidelity International

Chart: Charles Michelin

Why Inflation Got So High

UK Inflation rose because of several overlapping waves hitting the economy between 2020 and 2024

Global energy and supply chain shocks:

Post-COVID supply chain disruptions

After the lockdowns, global supply chains struggled to restart: factories in Asia reopened slowly, shipping costs surged and delivery times exploded. ONS

The result was:

- shortages of intermediate goods ONS

- significant price increases on imported components CarryCargo

- delays in production for UK firms

This was especially damaging because the UK relies heavily on imported goods, from electronics to clothing to machinery. National Preparedness Commission

So, when global prices increase, the UK feels it quickly.

The Ukraine war and the energy shock

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine generated a massive spike in natural gas prices.

The UK is particularly exposed because:

- households rely heavily on gas heating

- the UK imports a significant share of energy

- market price changes reach consumers quickly

- This pushed the CPI energy component to record highs in 2022–2023.

Domestic labour shortages (Brexit):

Before Brexit2, EU citizens could move to the UK and work there without needing a visa.

It changed after Brexit: according to the UK Government, “Free movement between the UK and the European Union ended on 31 December 2020” and the UK introduced a new points-based immigration system in January 2021, requiring work visas for EU nationals. Gov.uk

As a result, large numbers of workers in hospitality, construction, agriculture, logistics, health and social care could no longer enter the UK labour market as easily as before and so, lost access to a large part of their usual workforce. Gov.uk

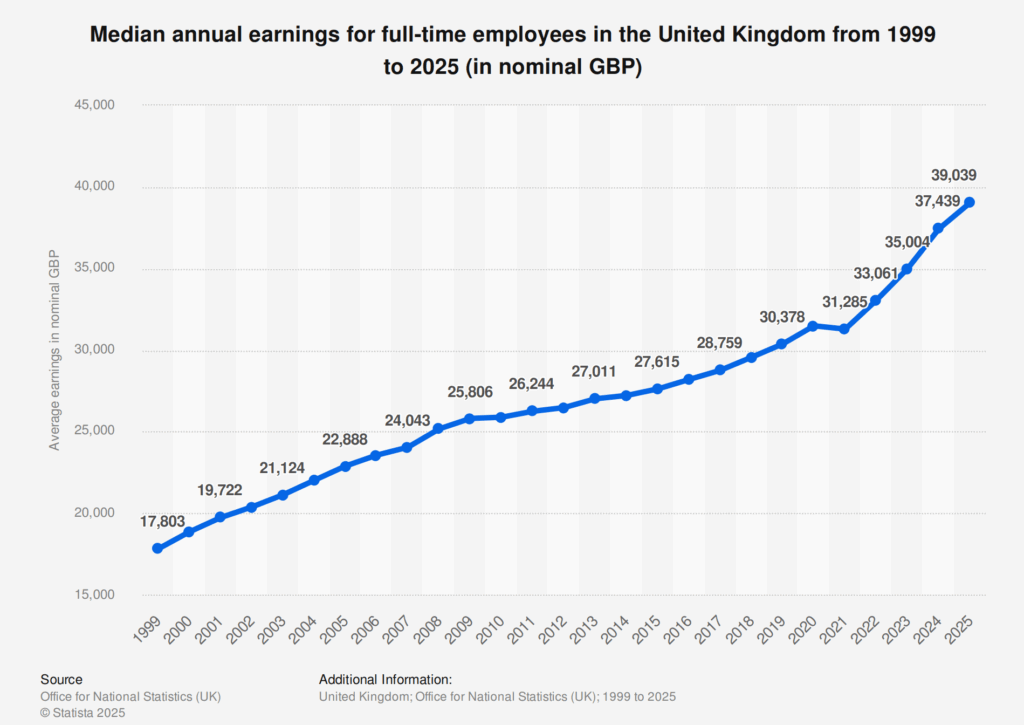

With fewer EU workers available, businesses struggled to fill vacancies. Firms had to raise wages to attract staff, and these higher labour costs were often passed on to consumers through higher prices. CIPD Report

On top of these structural issues, the UK became less attractive to European workers due to higher administrative costs, more paperwork, and a political environment perceived as less welcoming after Brexit. Many EU citizens simply chose to work elsewhere in Europe. Migration Observatory

These labour shortages contributed to higher and more persistent inflation, even after the energy shock began to fade. With fewer workers, higher wages, and reduced supply capacity, price pressures remained strong in several industries, making the UK’s inflation stickier than in many comparable European economies. Centre for European Reform

Strong post-pandemic demand

During the COVID lockdowns, UK households accumulated excess savings because they were spending much less than usual and receiving exceptional government support. This came from:

-reduced day-to-day consumption

-the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (furlough payments)

-temporary rent and mortgage relief in several regions

When the economy reopened, demand surged extremely fast, particularly in:

- travel and tourism

- hospitality

- retail and leisure

But supply capacity was still constrained: global supply chains were not fully restored, firms faced labour shortages, and inventories were low. Companies reacted by raising prices sharply, as demand was rising faster than supply could recover. Bank of England , IFS

This strong “demand rebound” created a clear case of demand-pull inflation, meaning prices rose because consumers were spending aggressively. It came on top of existing cost-push inflation from energy and goods shortages, compounding the overall inflation pressure in the UK.

Long-term UK structural weaknesses

Even before COVID and Brexit, the UK already faced deep structural issues that made the economy more vulnerable to inflationary shocks. The Economy 2030 Inquiry

Weak productivity growth

The UK has experienced persistently weak productivity growth since the mid-2000s, often referred to as the “productivity puzzle”. Low productivity limits how well the economy can absorb rising costs. It makes the country more exposed to:

- supply shocks

- rising wages

- increases in external costs (energy, imported inputs)

The Productivity Institute , Office for Budget Responsibility

High dependence on imports

The UK imports a large share of its goods (65.0% of total UK imports in 2024), including food, electronics, machinery, and energy. Gov.uk

Because of this dependence:

- global price increases feed into UK inflation more quickly

- a depreciation of the pound makes imports more expensive, amplifying inflation

This structural reliance on imports means international shocks pass through rapidly to domestic prices.

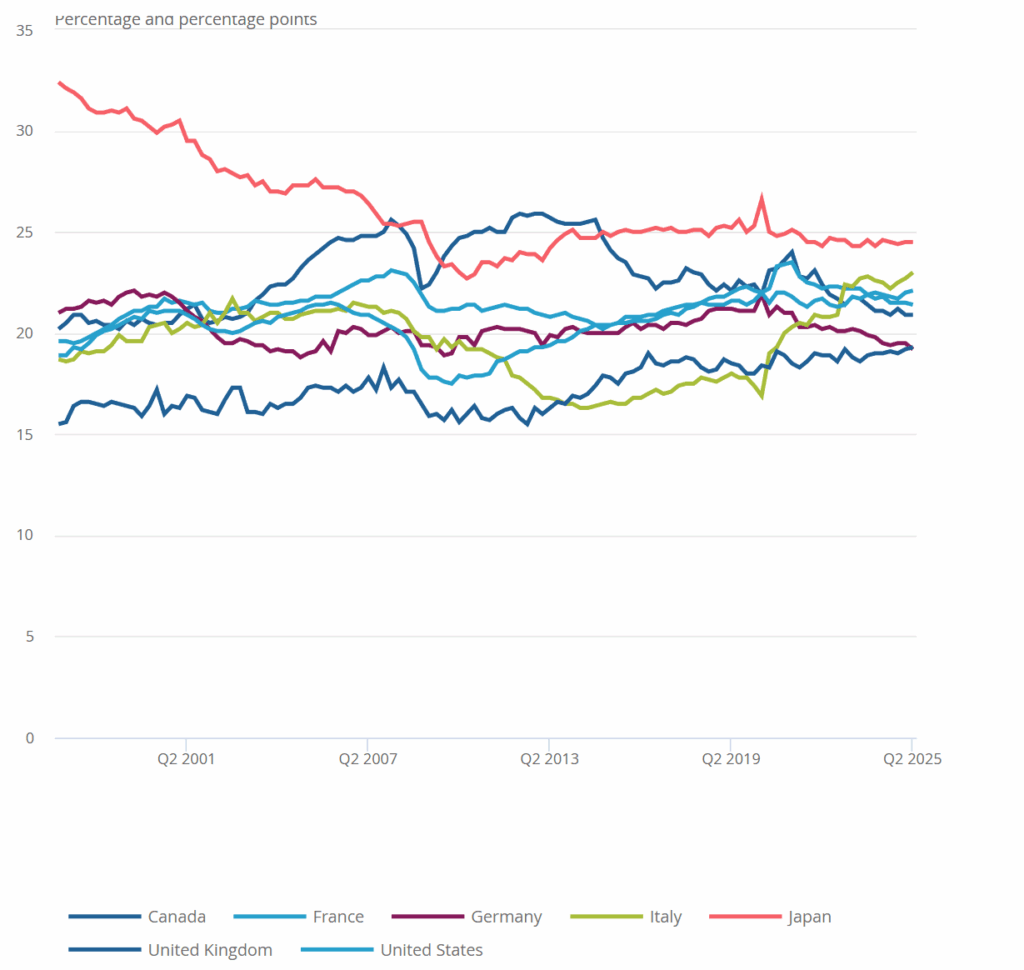

Chronic underinvestment

For many years, the UK has invested less than other major developed economies, both in the public and private sectors.

According to Green Alliance: “The UK has a long term underinvestment problem. Annual UK total investment, as a share of GDP, has been on average four percentage points below that of other G7 economies since 1990. “

This persistent gap makes it harder for the UK to innovate, boost productivity and keep up with changing economic needs.

What the Bank of England Has Done

From 2021 to 2023, the Bank of England raised interest rates aggressively, moving the Bank Rate from 0.1% to 5.25% in order to counter the strongest inflation shock in decades. Since August 2024, the BoE has gradually begun cutting rates, bringing the Bank Rate down to 4.0%. UK Parliament , The Guardian

Chart: Charles Michelin

The objective of these tightening measures was to address both excess demand and supply-driven persistent inflation.

The BoE’s Policy Tools to Reduce Inflation

The Bank of England relies on three main instruments:

These tools shape financial conditions, influence market expectations, and help guide inflation back to target.

Why Cut Rates While Inflation Is Still Above 2%?

The first point is that a 4% Bank Rate is still restrictive.

Even if the BoE cuts slightly, this level of interest rates continues to put downward pressure on inflation.

To understand this, it helps to look at the neutral real interest rate (r*)6, which the Bank of England estimates to be close to 1%. Bank of England (Chart 4)

So if the policy rate is at 4%, it stands well above this neutral real interest rate, meaning it slows the economy.

A key element is that interest rate changes do not affect the economy instantly. Their full impact usually takes 12 to 18 months. Bank of England (page 2)

This means that the UK is still absorbing the effects of the aggressive hikes from 2022-2023.

So even with a small 25 bps cut, monetary policy remains tight.

The BoE isn’t stimulating the economy, it is simply reducing some of the pressure.

This is why the BoE focuses on future inflation rather than the current number: monetary policy needs to be forward-looking.

Another point is that keeping interest rates elevated until inflation returns to exactly 2% could do more harm than good. This is the risk of overtightening: when policy stays restrictive for too long. Reuters

Because of these long lags, waiting until inflation is exactly at 2% would be too late.

The economy would continue to slow for another year, even after cuts. This could lead to:

- unnecessary economic weakness

- higher unemployment

- inflation falling below target

- a higher probability of recession

Where Things Are Heading?

UK inflation continues to ease but is still above the BoE’s 2% target, which reflects the lingering effects of energy shocks, Brexit-related labour shortages and long-term structural weaknesses.

With the Bank Rate at 4%, monetary conditions remain restrictive, which helps to rein in demand and slow wage growth.

The next Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting is scheduled for 18 December and according to Reuters, markets expect another 25 bps cut. Reuters

Update (18 Dec): The MPC voted 5-4 in favour of a 25 bps rate cut, lowering the Bank Rate to 3.75%. BBC

According to the Bank of England (Bank of England page 5), “Inflation is likely to fall to close to 3% early next year before gradually returning towards the 2% target over the subsequent year”.

For now, investors appear confident that the worst of the inflation shock is behind the UK, but the BoE remains cautious.

- The Monetary Policy Committee is the body within the Bank of England that sets monetary policy to keep inflation close to the 2% target. ↩︎

- process by which the UK left the EU, formally completed on 31 January 2020 after the 2016 referendum, in which 51.9% voted to leave (The Electoral Commission) ↩︎

- Gross Fixed Capital Formation: represents the investment made by firms, households, and governments in durable goods that are used for more than one year in the production process.

↩︎ - it is a monetary policy that removes liquidity from the economy to slow down inflation.

↩︎ - it is a communication policy through which the CB signals in advance how it intends to adjust interest rates or monetary policy in the future ↩︎

- It is the real interest rate that keeps the economy in balance (meaning neither speeding up nor slowing down). ↩︎