Understanding the Greek Sovereign Debt Crisis: Structural Weaknesses, Market Shocks and Policy Responses

The European sovereign debt crisis that erupted starting in 2010 originated from imbalances that had accumulated over several decades.

To understand it, we must first define sovereign debt: it is the debt of the State, meaning all the loans that the government takes out to finance its expenditures, whether salaries, pensions, infrastructure, healthcare, or education.

The general structural causes include:

- The deterioration of public finances in many countries, linked to the slowdown in economic growth since the 1970s, which limited revenues while public spending continued to rise (for example pensions and healthcare).

- Weak economic growth in European countries, with insufficient tax revenues to finance rising public expenditures.

- High levels of public spending (social protection, healthcare, pensions…).

- Debt that accumulated year after year, as governments financed their deficits (the state spends more than it earns in a given year) by borrowing.

In addition, with the introduction of the euro in 1999, the credibility of EU member states increased because by sharing a common currency, investors perceived less risk than when national central banks were managing things individually.

This decline in perceived risk led to a sharp drop in interest rates, which encouraged many European countries to borrow even more, as it had become much easier and cheaper to take on debt. ECB

But the 2008 subprime crisis was the final shock, causing government revenues to collapse and public spending to surge, as governments had to support their economies in free fall: stimulus packages, unemployment benefits, and bank bailouts.

This multiplication of expenditures only worsened budget deficits and increased the debt of European states.

Trigger: Greece, the first domino (2009–2010):

Why was Greece vulnerable before 2009?

At the end of the 1990s, Greece wanted to join the Eurozone, so it had to meet the Maastricht criteria stating that the country must:

- control inflation

- have public debt below 60% of GDP

- have a public deficit of at most 3% of GDP

- interest rate convergence1

- exchange rate stability2

On paper, Greece was far from meeting these goals: a deficit above 4%, debt already over 100% of GDP, and unreliable public accounting and statistics. World Data

But entering the euro area offered Greece a decisive advantage: much lower borrowing rates than those a small economy like Greece could obtain on its own, allowing it to finance its debt much more cheaply.

Athens then made sacrifices to appear ready to join the EU.

Starting from 1998, the government inflated state revenues, underreported expenditures, and reclassified certain debts into obscure public entities, with the help of the bank Goldman Sachs, which set up a very sophisticated financial engineering operation. This allowed Greece to receive several billion euros in exchange for future revenues from highway tolls, airports, etc., which did not yet appear in the government’s accounts. The Guardian , IMF eLibrary

This created the illusion that state revenues were rising while expenditures were not increasing.

The whole transaction was presented as a short-term currency swap, meaning it did not appear as a loan.

Result: in Brussels’ spreadsheets, the deficit artificially went back under 3% of GDP and the debt appeared to shrink.

On this operation, the American bank earned about 300 million dollars in fees. Business Insider

The euro authorities, not very strict at the time, approved the accounts, and on January 1st, 2001, Athens secured its ticket to the euro.

Thanks to the single currency, Greece was now attached to the financial credibility of the ECB, itself supported by the credibility of countries like France and Germany.

Investors then perceived Greece as less risky, and the country benefited from a wave of cheap credit. Bank of Greece

Greece entered a period of growth, rising consumption, and a booming real estate market. LSE

Yet, the signs of bankruptcy were obvious for anyone who wished to see them:

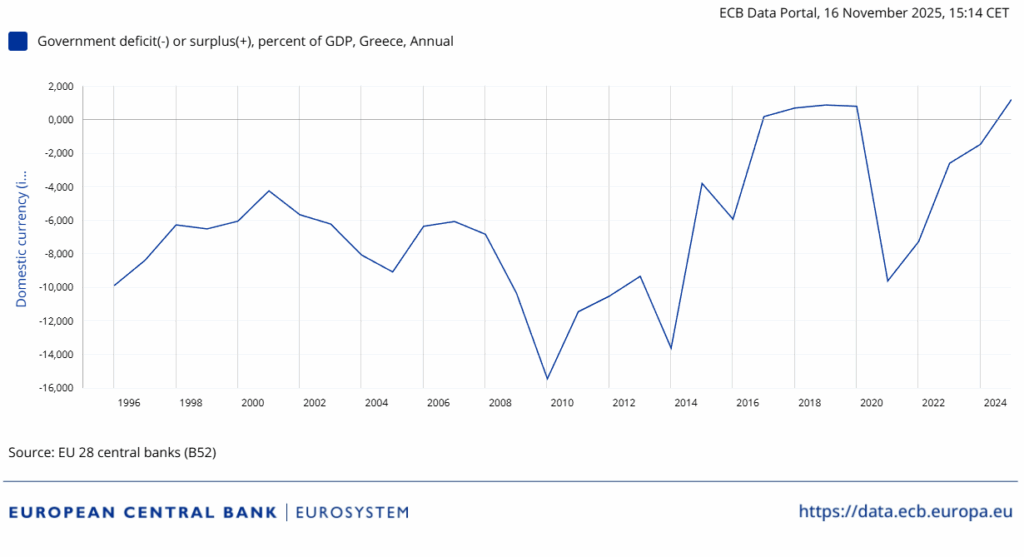

- Greece’s deficit in 2001 was 5.6% of GDP.

- Public debt was already at 110% of GDP.

Despite an already disastrous budgetary situation, the country hosted the 2004 Olympic Games, an event whose total cost is estimated at around 9 billion euros.

These expenses further increased the public deficit, which went from 8% in 2003 to 9.1% of GDP in 2004. The Guardian , ECB

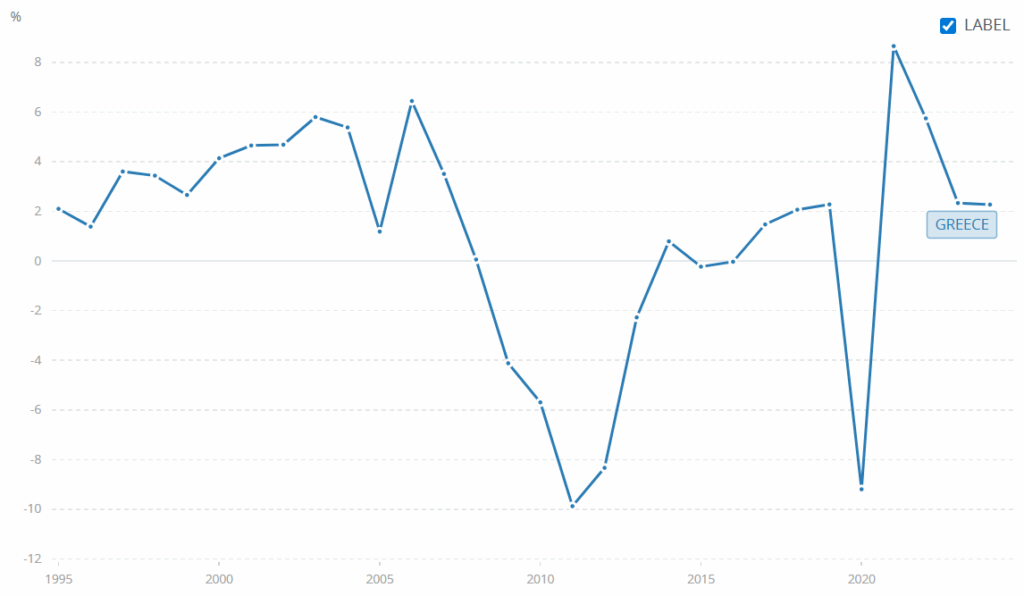

However, in 2004, Greece’s GDP grew by 5.4% compared to 2003, but this growth masked a deep deterioration of public finances. CountryEconomy

The markets turned a blind eye and continued lending because the global economy was booming.

Athens kept borrowing, thinking it would deal with the bill later.

The shock of 2009: everything collapses

In 2008, the music stopped, and it was time for Greece to pay the bill. The global financial crisis erupted and ended the illusion of prosperity.

Banks stopped lending, markets froze, and external financing dried up.

From 2009 onward, Athens could no longer refinance its colossal debt.

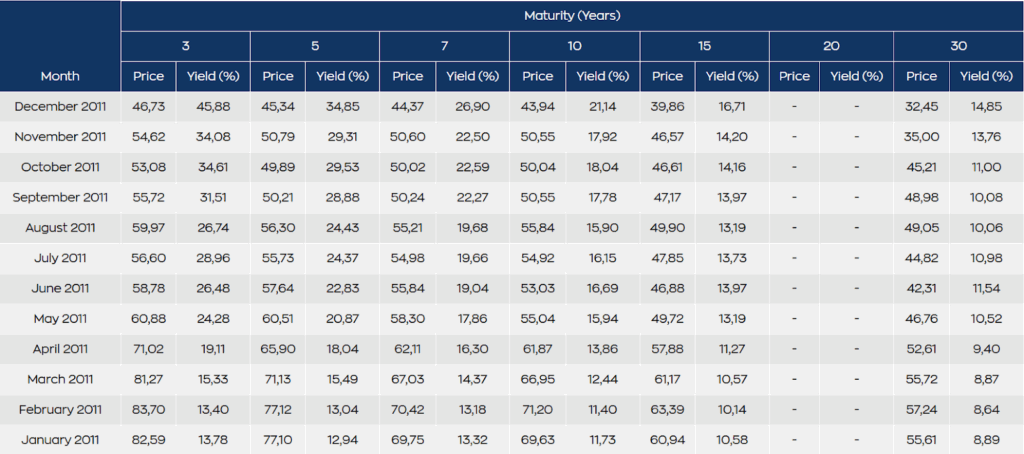

Interest rates on Greek government bonds (GGBs3) skyrocketed. As they were seen as risky, investors refused to buy them, and the country was on the verge of default.

New government

In this particular context, in October 2009, the new Greek Prime Minister, George Papandreou, dropped a bombshell: he announced that the Greek budget deficit had been massively underestimated and that instead of the officially announced 6% of GDP, it would exceed 12%.

A few months later, the final estimate came out: the 2009 deficit reached 15.4% of GDP, an absolute record for a Eurozone country. ESM , ECB

The true situation of Greece finally became visible, and market confidence collapsed.

In April 2010, rating agencies downgraded Greek sovereign debt to junk status: “junk bond”, meaning that lending money to Greece was economic suicide, extremely risky. The Guardian

Investors fled, and the only ones willing to lend demanded enormous interest rates to compensate for the risk: up to 18% and even more than 40% per year in extreme cases. Ekathimerini

Nobody is lending to Greece anymore, Athens is cut off from the financial markets, and bankruptcy is inevitable. ESM

To avoid the implosion of the eurozone, the EU and the IMF then triggered a series of bailout plans.

The 3 bailout programmes (2010, 2012, 2015)

First Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece (2010):

Europe panicked, as such a bankruptcy would weaken the credibility of the entire eurozone.

In addition, a Greek default would cause enormous losses for French and German banks, which were heavily invested in Greek debt.

In spring 2010, Greece asked for help for the first time, and on May 2nd, its EU partners, with the support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), rushed to its rescue with a first bailout plan worth 110 billion euros. France24

Germany alone contributed 22 billion euros to this plan. Council Foreign Relations

In exchange for this loan, the Troika4 demanded an unprecedented austerity programme.

The Greek government committed to a massive fiscal effort corresponding to more than 12% of GDP over 3 years, through tax increases and cuts in public spending.

With a GDP of around 223 billion euros in 2010, this represents roughly 27 billion euros of fiscal adjustments. Country Economy , IMF

This meant that over the following 3 years, public sector wages were cut by about 20%, pensions were reduced, the legal retirement age was raised from 65 to 67, VAT increased from 19% to 23%, income tax brackets rose, corporate taxes rose as well, etc. The Guardian , The Guardian

Finally, public services saw their budgets slashed drastically: education -23%, healthcare -24%, and in local administrations, 50% of staff were laid off. European Comission

Economic and social consequences of austerity:

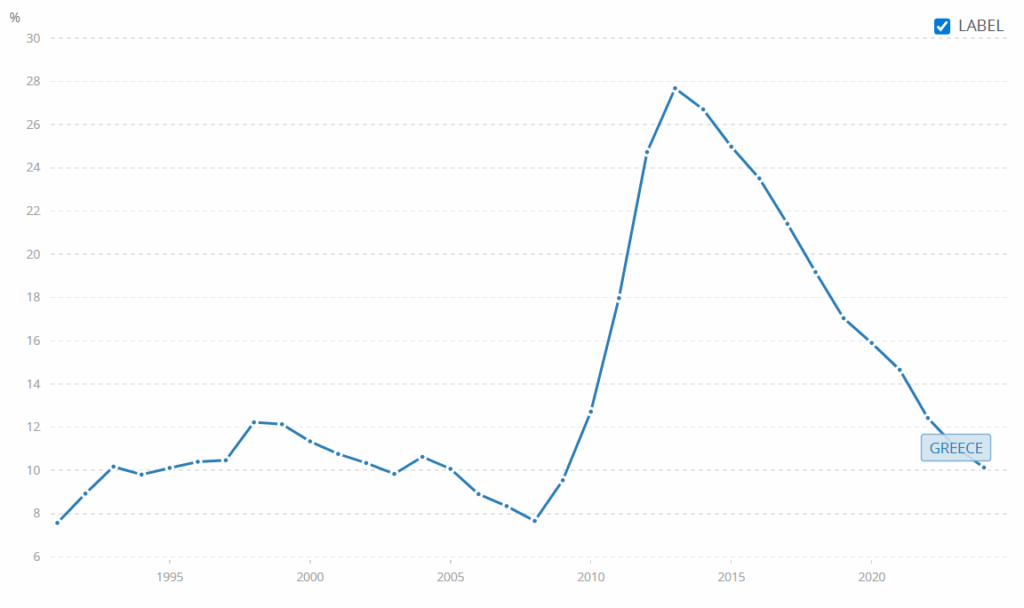

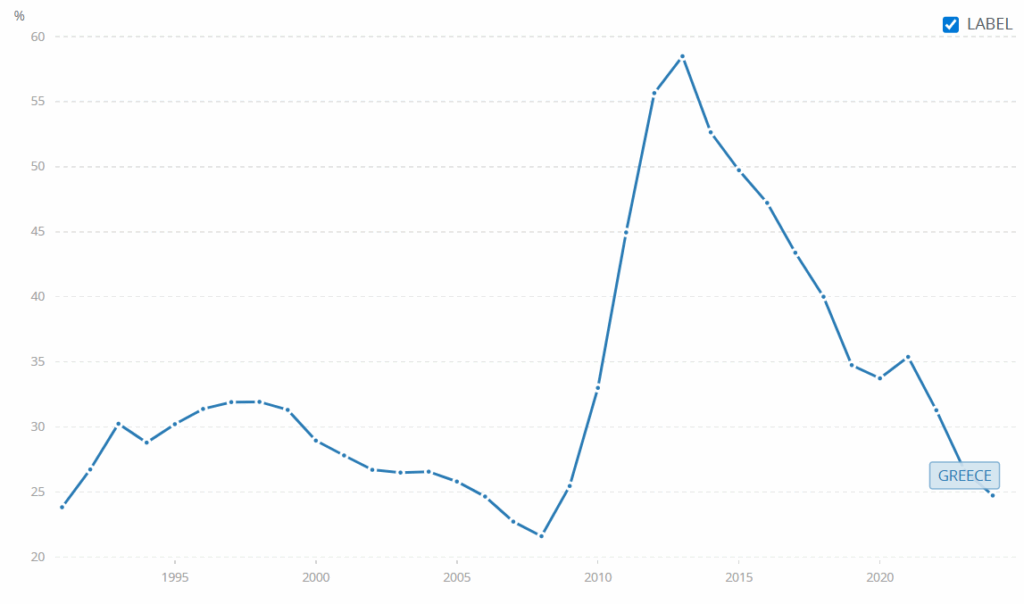

Massive shock: the Greek economy, which had been artificially fueled by debt for 10 years, fell into a total recession.Within a few years, GDP collapsed by around 25%, unemployment exploded to over 24% of the labour force, thousands of businesses closed, private-sector wages plummeted, and riots and protests paralysed the country. Eunews

Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece (2012):

In 2012, the situation was still just as bad. Greece still needed money to repay its creditors, and a second, even more ambitious bailout plan of 130 billion euros was put in place. IMF

This time, creditors (people who owned Greek debt, such as banks or investment funds) were asked to contribute and accepted a 53% haircut on the value of their bonds. It was either they accepted, or Greece would default and they would recover 0 euros, or almost. ESM

A major default and a historic first. Never before had a country partially defaulted in this way. CEPR

Thanks to this, the Troika hoped to bring Greek debt down to a more acceptable level of 120% of GDP by 2020, compared to more than 160% of GDP in 2012. Reuters

In exchange, Athens had to continue and intensify austerity, notably through a wave of privatisations to bring money into the state’s coffers.

Despite these efforts and bailouts, Greece remained caught in a vicious cycle of recession and debt.

By 2014, after 4 years of austerity, Greek public debt was still hovering around 180% of GDP, and unemployment was still around 26.4% of the labour force. Données Mondiales , WorldBank

An entire generation of young people found itself with no future prospects, hit by more than 50% youth unemployment, and forced to leave the country to find work.

Social and political consequences:

There were dozens of general strikes, sometimes paralysing the country for several days, with up to 500,000 people in Athens, knowing that the country had around 10 million inhabitants at the time. These protest movements were very popular, with around 90% of the population supporting them.

The political crisis and the showdown with Europe (2015):

In January 2015, the Greeks brought to power the radical left party Syriza, led by the young Alexis Tsipras, who was 40 years old at the time.

Syriza won a sweeping victory and put an end to 40 years of alternation between socialists and conservatives. The Guardian

The message was clear: the population refused to continue on the path of austerity at all costs, and during his campaign, Tsipras promised to stop the humiliation imposed by the Troika. His government announced that it wanted to renegotiate the bailout conditions, cancel part of the additional debt, and revive growth by loosening budgetary constraints. Aljazeera

In short, he promised to give Greeks back their dignity and sovereignty in front of the creditors, basically a return to the life Greeks had before.

Rising tensions and capital controls:

Very quickly, total disillusionment set in. Greece’s European partners, led by Germany, which had directly lent money to Greece several times and had major weight within the EU, categorically refused to cancel Greek debt or allow the deficit to widen. WEF

For them, it was out of the question to create a precedent that could encourage other European countries like Italy or Spain to spend uncontrollably.

A tense showdown began in February 2015 between the Tsipras government and Europe. VOA

The Greek finance minister held multiple heated meetings with his European counterparts, defending Greece’s right to cancel a large part of its debt, especially the portion borrowed a few years earlier from Europe.

As the months went by, the situation worsened, bank withdrawals accelerated, and the state treasury melted away.

At the end of June 2015, Athens ran out of money and missed a 1.6-billion-euro payment to the IMF, becoming the first developed country to default on the Fund. The Guardian , ITV

At that moment, fearing a banking collapse and a euro exit, Greeks rushed to the banks to withdraw their savings in cash.

To avoid the collapse of the banking system, Alexis Tsipras was forced to close the banks and impose capital controls starting on 28 June 2015. SSRN

From then on, transfers abroad were blocked and ATM withdrawals were limited to 60 euros per day.

Despite this very harsh situation, hope among the Greeks remained.

Referendum and Grexit scenario:

On the edge of the cliff, Alexis attempted one last move: he announced the holding of a national referendum on the latest proposals from the European creditors.

In other words, he asked the Greek people whether they accepted or not the austerity measures in exchange for the 3rd bailout plan.

They voted on July 5th, 2015, and the result was clear: around 61% of voters said “OXI”, meaning NO to the new austerity measures. The Guardian

People celebrated the NO vote, interpreted as a sovereign refusal to continue the austerity imposed by foreign creditors.

As Tsipras said, the people stood firm.

This euphoria was short-lived. The reaction from the eurozone countries was ice-cold. European leaders said that no one was going to pay indefinitely for Greece, and that the choice was simple: either Greece accepted even tougher reforms in order to access a 3rd bailout plan, or Europe would refuse to grant any new loan. Cogitatio

Since nobody else wanted to lend them money, not even the IMF, a refusal from Europe would force Greece to leave the single currency in order to regain control of its own currency and be able to print money to pay salaries, pensions, public spending, etc.

But why is this not possible for Greece?

The idea is appealing, but the problem is that Greece is a bankrupt country, and the credibility of a currency depends on the credibility of the central bank of that country.

So if Greece leaves the euro, the drachma, which is the Greek national currency, would have no value.

Who would trust the currency of a bankrupt state that, through a referendum, decides to stop austerity and not repay its debt?

Nobody wants a currency from a country whose value depends on a government unable to balance its budget and planning to print money to finance the entire economy.

According to estimates, if Greece had left the euro at that moment, the drachma would have lost at least 50% of its value on the very first day compared to the euro. In other words, the purchasing power of all Greeks would have been cut in half immediately. WEF

So it would have been a bad idea.

Third bailout plan and supervision :

Tsipras therefore capitulated.

Against all expectations, the Greek prime minister accepted on July 13th, 2015 a new bailout plan worth up to 86 billion euros, of which 61.9 billion would be disbursed between 2015 and 2018, with conditions even stricter than those rejected by the Greeks in the referendum only eight days earlier. European Council

This was harsh for both the population and the government.

The referendum therefore made the situation worse and closed the door to negotiations.

Alexis rushed the new austerity plan through the Greek parliament, including further tax increases and significant budget cuts in order to satisfy Europe’s demands. ABC

This decision caused a split in his party, and some MPs called him a traitor for having betrayed the popular verdict.

The finance minister resigned the day after the referendum, disagreeing with the government’s U-turn. Aljazeera

However, in September 2015, new elections were held, and Tsipras was re-elected narrowly, promising to do better.

But at that moment, one thing was certain: the dream of an alternative to austerity was dead. The balance of power in Europe and economic reality had caught up with Greece.

Greece found itself under the economic supervision of its European creditors, who would monitor in the long term whether the country respected its commitments.

Official end of the Greek crisis: 2018

It may seem hard to believe, but during this crisis, even after two austerity plans, the Greek deficit was still large.

In 2012, for example, the public deficit was still 8.7% of GDP, less than before but still enormous.

In other words, even with the two austerity plans, Greece was still living beyond its means.

It was finally in 2015, after the 3rd austerity plan, that the situation slowly stabilised. Through repeated sacrifices, Greece managed to regain positive economic growth.

And in August 2018, the country officially exited the international assistance programme, marking the announced end of the Greek crisis, nearly 10 years after it began.

In total, the country received around 290 billion euros in aid since 2010, more than its 2024 GDP. Country Economy

Although Greece exited the EU’s enhanced surveillance in 2022, it remains under PPS, which involves regular monitoring until it has repaid 75% of its European loans. Euroactiv , Post-Programme Surveillance Report

What This Crisis Really Teaches Us?

The Greek crisis shows how hidden imbalances always end up exploding. By entering the euro thanks to accounts masked with Goldman Sachs, Greece was able to borrow cheaply for years. But the 2008 crisis revealed the true state of its finances: markets turned against it, the country lost access to funding, and had to be rescued by the EU and the IMF. The austerity plans that followed plunged the economy into a deep recession. In the end, the Greek crisis reminds us that the stability of the eurozone is built on transparency and fiscal discipline.

- The interest rates of Greece (the rates at which the State borrows) had to move closer to those of the most stable countries in the EU, especially Germany. Greece therefore had to bring its interest rates down by reducing its perceived risk (inflation, deficit, instability).

↩︎ - Greece had to prevent its currency, the drachma, from falling (relative to the euro) by maintaining a disciplined monetary policy. ↩︎

- Greek Government Bonds ↩︎

- Alliance composed of the European Commission, the ECB, and the IMF. ↩︎