Inside France’s Debt Machine: How the State Really Finances Its Deficit

France runs a deficit almost every year, and to keep functioning, the it must constantly borrow money on financial markets. But how does this borrowing actually work? Who buys France’s debt, why do they keep doing it, and what limits does the country face as its debt keeps rising?

To understand all this, we first need to look at how the French State actually finances its deficit.

How does the French State finance this deficit?

The French State finances it by borrowing on financial markets, from investors who buy its debt:

- banks

- investment funds

- insurance companies

- pension funds

These investors buy government bonds (in France, OATs1), issued by the AFT2.

The Agence France Trésor uses an auction to sell these OATs to investors.

Concretely, the State announces that it will issue X billions of bonds on a given date. Banks and investors send their offers (how much they want and at what price), the AFT then selects the best offers and the bonds are then allocated to the buyers, allowing France to receive the money in order to finance its deficit. In exchange, the State promises to repay them later by paying interest every year. CGT

The AFT does not decide the deficit nor the amounts to be borrowed: it simply applies the financing voted by the government and the Parliament. Assemblée Nationale

Can a sovereign State decide to issue new bonds whenever it wants?

Yes, technically nothing prevents it, the State can issue new bonds whenever it wants, but in reality, it faces several economic, financial and institutional limits that condition its ability to finance itself…

Limit 1: investors:

It is nice to issue bonds, but investors still need to accept to buy them.

If the State’s debt becomes too high or too risky, investors will therefore demand higher interest rates or will stop buying, but they can also require tougher conditions or simply turn to countries considered safer.

A State cannot force an investor to buy its debt!

Limit 2: the interest rate:

It is important to know that the higher a State’s debt goes, the more the market demands higher interest rates in order to compensate for the repayment risk.

This creates a vicious circle:

The State issues more debt → investors demand higher interest rates → interest payments become more expensive for the State → the State’s deficit increases → the State must issue even more debt to finance its deficit → interest rates rise again since the debt increases…

This is what happened to Greece in 2010, they were no longer able to borrow from investors at reasonable rates, which caused the Greek economy to collapse and triggered the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone (see article on this).

Limit 3: rating agencies:

S&P, Moody’s, Fitch can downgrade France’s rating, which would lead investors to demand higher rates.

Limit 4: avoiding a confidence crisis:

If everyone thinks that France will no longer be able to repay, no one will buy its debt anymore, rates will explode, the State will no longer be able to finance itself and this would lead to a sovereign debt crisis.

“Fortunately”, France is protected by its size, its economy, its credibility, the euro and the fact that the ECB is ready to stabilize markets (OMT program).

Limit 5: EU rule: Maastricht Treaty (1992) and Stability Pact (1997)

France, like the other EU countries, must respect:

- a deficit ≤ 3% of GDP

- a debt ≤ 60% of GDP European Council

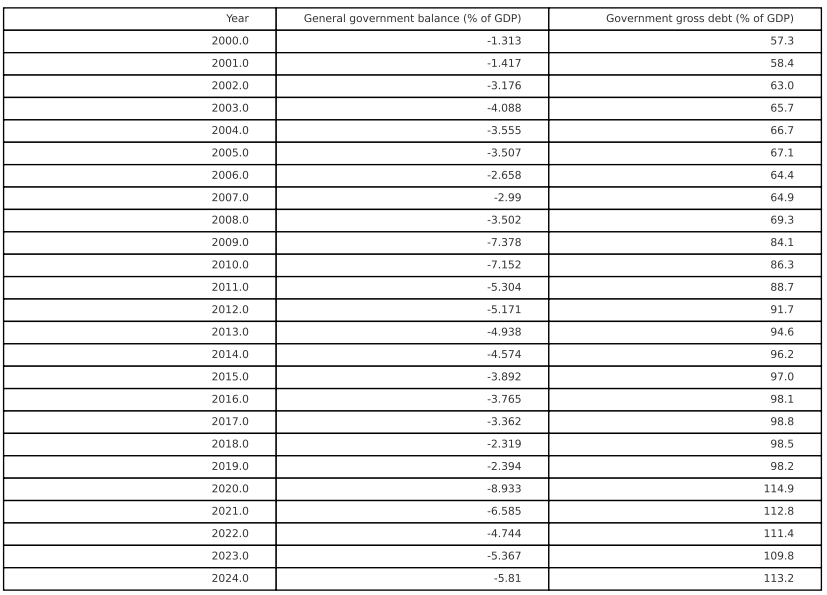

Which it does not really do (see table above).

But why do investors continue to buy French debt despite this?

Even with debt > 110% of GDP, which goes against the EU stability pact, investors continue to buy it, surprising, here are the reasons:

→ France is considered a very safe issuer, it has not experienced a default since 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic wars, more than 200 years. Banque de France

→ The ECB supports States, it has massively bought government bonds since 2015 (QE3) and it has a commitment: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”, Mario Draghi4, 2012, words he said during a speech to reinforce the idea that the ECB will not let a country collapse. ECB, ECB

→ OATs are very liquid, rated AA5, and are considered safe assets, they are called a “core asset” for investors. When French debt increases, investors may demand higher rates to compensate for the additional default risk. This may offer higher returns to new investors, but it also reflects an increase of the risk associated with France. Scope Ratings, AXA

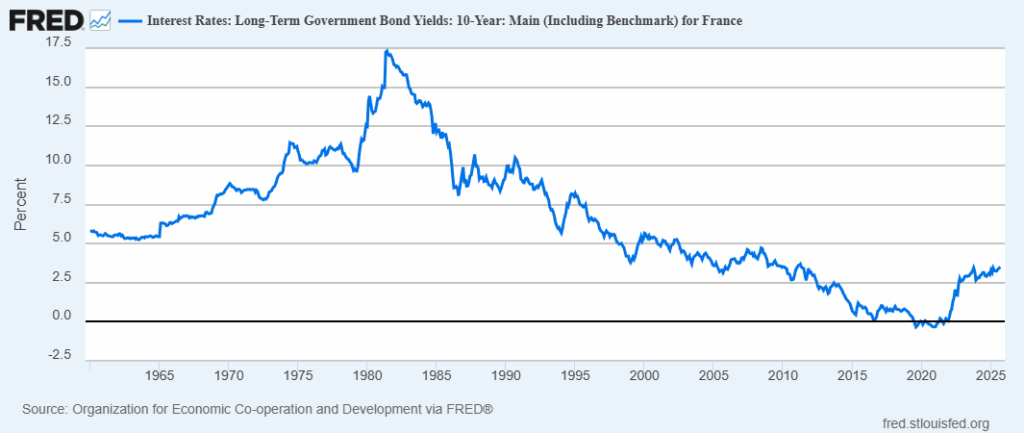

→ Rates have become attractive again: Before 2022, rates were close to 0%, sometimes even negative, which made French bonds much less profitable and therefore less attractive. Since 2022, OATs now offer a higher yield, around 3-3.5% on 10 years, which for a country rated AA is very attractive.

→ European rules (Basel, Solvency II): Banks must hold a large stock of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA6) to meet the liquidity ratio (LCR). On their side, insurers, under Solvency II, are not required to hold them, but well-rated sovereign bonds of the euro area, including OATs, benefit from a very favorable regulatory treatment, which encourages them to hold a significant share of them in their portfolio. ECB

So, even if they are not obliged to buy OATs, these institutions have every interest in buying safe sovereign debt (France, Germany, Netherlands, Austria).

France can still borrow despite these limits.

The central question remains: why does it need to borrow every year and continue increasing its debt?

Why is France always in deficit?

A very high level of public spending

France has one of the highest levels of public spending in the developed world (about 57% of GDP in recent years, according to recent budgets). Banque de France

→ a lot of social spending (pensions, health, unemployment, minimum benefits)

→ a very present State (public sector, education, defense, etc.)

→ economic support (subsidies, support to certain sectors)

Reducing these expenses is politically very complicated → governments postpone.

Successive shocks that widened the debt

For the past 20 years, there has been a succession of shocks where we did the “whatever it takes”:

→ financial crisis 2008–2009

→ eurozone crisis

→ Covid crisis (2020–2021)

→ energy crisis, inflation (2022)

These shocks push the State to spend more without increasing revenues as much, which mechanically widens the deficit.

As a result, year after year, France spends more than it collects in taxes.

This deficit must be financed somewhere.

How does France finance its deficits and this accumulating debt?

To finance France, the AFT does not only issue OATs, it also issues BTFs, which unlike OATs, are very short-term securities with a fixed rate and discounted interest7 (3, 6 or 12 months) mainly used to manage the State’s cash position. Agence France Trésor

The last time France had a budget surplus was in 1974, when France had a public debt of about 30.4 billion euros, or 14.5% of GDP. Fondation IFRAP

Since then, the situation has completely reversed.

At the end of the second quarter of 2025, public debt stood at 3,416.3 billion euros, or 115.6% of GDP. Gouvernement

Faced with this growing debt, the State’s financing needs mechanically increase:

According to the figures of the Agence France Trésor, the State issued in 2024 a total of €541.1 billion of bonds: €339.9 billion in medium and long term (via OAT and OATi) and €201.2 billion in short term (via BTF). AFT

Yet, according to the Cour des Comptes, the total financing need of the French State in 2024 was “only” €305.6 billion. This difference is explained by the fact that AFT issuances serve to cover both the annual deficit and the repayment of maturing debt.

In 2024, this represented about €155 billion of deficit and €151 billion of bonds reaching maturity, for a total of about €305 billion of required financing. Cour des Comptes , Cour des Comptes

France, like most developed countries, does what is called “rolling over the debt”: it issues new bonds to finance its annual deficit and to repay the old bonds reaching maturity.

This mechanism, repeated every year, allows France to maintain its financing without ever repaying the entire debt at once.

Why have French bond yields increased sharply since 2022?

The yields of OATs mainly increased because of the policy of the European Central Bank.

Most of the rise in yields is not due to a fear of default, but to monetary policy.

The two main reasons:

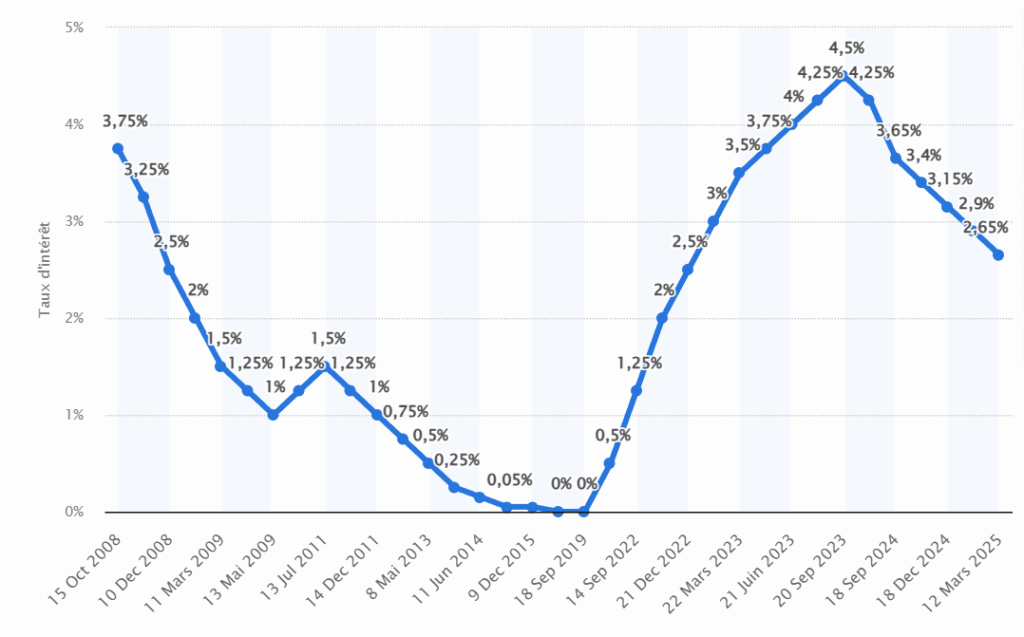

The ECB raised its key interest rates

Between 2022 and 2024, the ECB increased its key interest rates from 0% to 4%, all market rates in the euro area surged, which made French bonds attractive again, investors return to obtain a correct yield without taking too much risk.

By raising its key interest rates, all interest rates in the euro area automatically increased, whether for bank loans, government bonds or corporate bonds.

It is mechanical: when the ECB increases its key interest rates, borrowing becomes more expensive for commercial banks.

But banks finance themselves largely from the ECB or on the interbank market (where rates also follow those of the ECB).

So, if their borrowing costs increase, they must then pass this increase on to the loans they grant:

→ more expensive mortgage loans

→ more expensive loans to companies

→ higher government bond yields

Higher bond yields imply that older bonds, with rates lower than the new ones, yield less and therefore become less attractive, their demand decreases, making their price fall, which mechanically increases their yield.

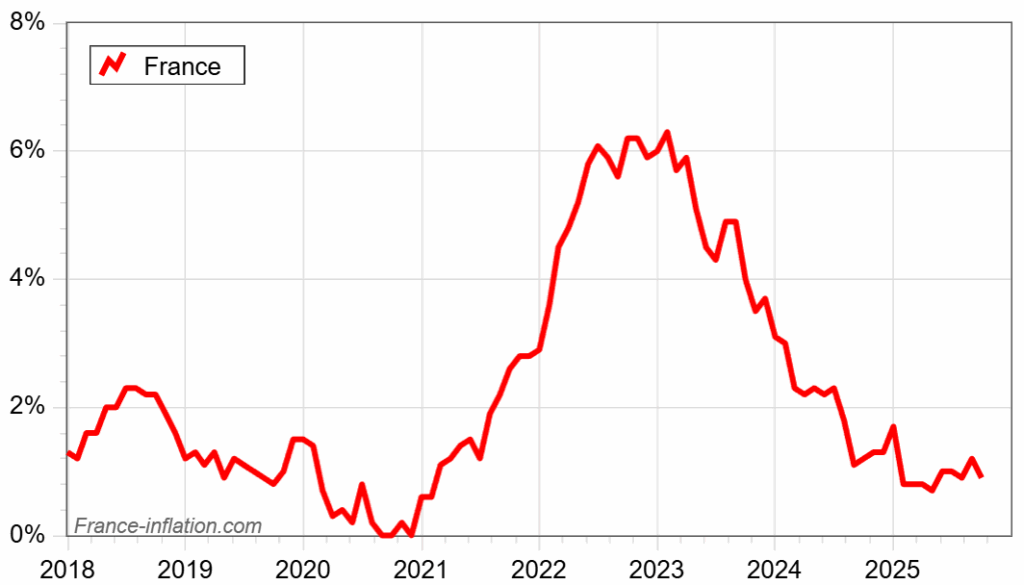

Inflation increased

When inflation rises, the value of money decreases.

Investors then demand a higher interest rate to be compensated and not lose money in real terms.

This is why, since 2022, with high inflation in the euro area, OAT yields (and all bond yields) have risen: investors want a return that protects their purchasing power.

A model running out of steam?

For more than 40 years, France has systematically spent more than it earns.

Year after year, deficits accumulate, even though France is already one of the countries that taxes its population the most, State revenues are still lower than its expenditures.

This observation reveals a structural problem: the model of French public finances no longer balances.

As long as investors continue to trust the State, France can continue to “roll over” its debt and finance itself without difficulty, but if nothing changes, the markets could begin to doubt France’s ability to control its finances, which closely reminds us of the scenario Greece experienced in 2010.

France will have to regain control of its finances if it wants to avoid the debt eventually becoming an uncontrollable problem.

- Obligations assimilables du trésor: Government bonds issued by the French State to finance its debt ↩︎

- Agence France Trésor: body of the Ministry of Finance, responsible for managing public debt, issuing OATs, speaking to investors and defining the financing strategy

↩︎ - Quantitative Easing: monetary policy of a Central Bank where the Central Bank buys bonds to inject money, lower bond interest rates and stimulate the economy

↩︎ - President of ECB (01.11.11 to 01.11.19) ↩︎

- Rating given by the rating agency S&P ↩︎

- High Quality Liquid Assets ↩︎

- the investor pays less than €100 at purchase and receives €100 at maturity. The difference = the interest, which is already included in the purchase price and not paid afterwards ↩︎